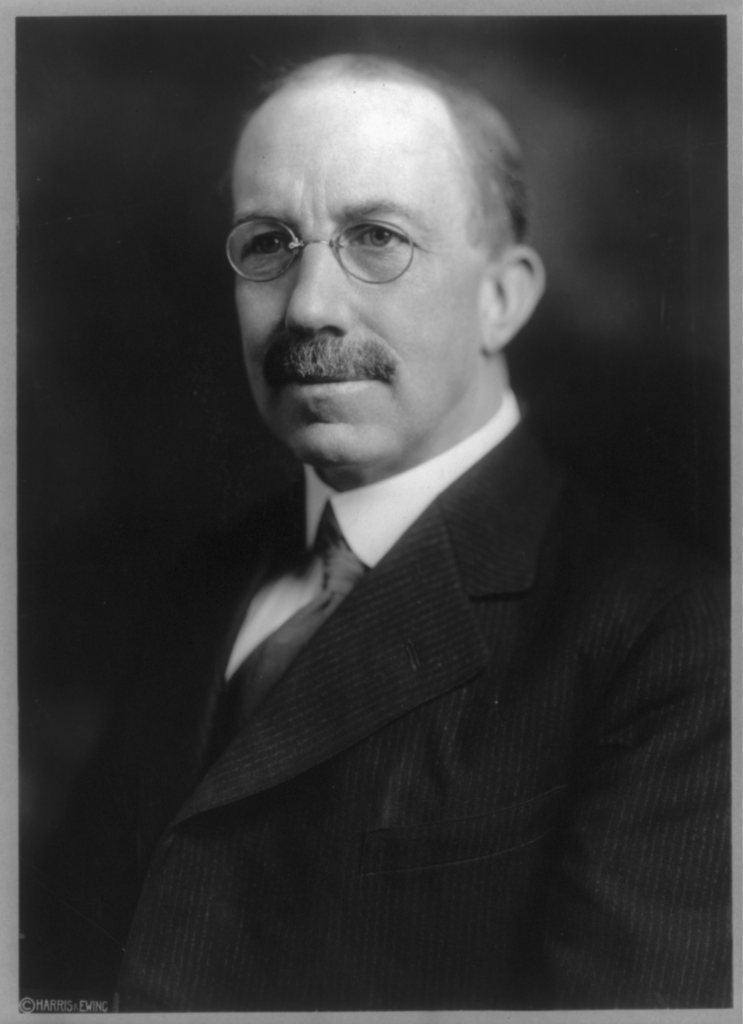

Wayne Wheeler, published by Harris &Ewing, via wikimedia

Wayne Wheeler was born in Ohio in 1869. While working on the family farm, Wheeler was stabbed with a hayfork by a drunk farm worker. This incident led Wheeler to a lifetime crusade against the consumption of alcohol.

When studying at Oberlin College, Wheeler was offered a part-time job with the Anti-Saloon League (ASL). It was an ideal job for him, and he continued in this position after college. While working for the ASL, Wheeler earned his legal degree.

Wheeler eventually became the legal counsel for the ASL, bringing lawsuits to restrict the production, sale, and use of alcohol. He subsequently rose to become the executive director of the ASL. He led the ASL to advocate for the prohibition of alcohol as opposed to treatment and education on responsible drinking.

Under Wheeler’s leadership, the ASL began to enter political campaigns and opposed candidates who did not support prohibition. This single-issue activism became known as Wheelerism and was used to target politicians, becoming an effective way to defeat candidates who did not support the ASL agenda.

When President Taft vetoed an early attempt at the prohibition of alcohol, the ASL had enough support in Congress to override his veto. The problem was that the federal government depended on revenue from alcohol sales. That changed with the 1913 enactment of the 16th Amendment, which authorized the federal income tax and reduced the government’s dependence on alcohol revenues.

The ASL was in a position to pass an amendment outlawing the production, sale, and use of alcohol. Wheeler worked in Congress to pass the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act in 1919 to enact the nation-wide prohibition of alcohol.

Eventually, Wheeler’s influence declined as the recognition grew that the prohibition of alcohol was ultimately unenforceable and led to more negative consequences than good. The growth of organized crime to skirt the prohibition and deaths caused by the poisonous bootlegged alcohol led to the repeal of the 18th Amendment in 1933.

While Wheeler lost part of his legacy when prohibition was repealed, he did leave another, the legacy of single-issue politics. It is a legacy that has become a plague on American democracy. Political organizations realized that they could drum up a sense of popular support for a single issue. They could then use this to apply pressure to political candidates by threatening to withhold campaign funds, or to fund rivals, unless the candidates played to constituents’ supposed single-issue obsessions. The ongoing inability of Congress to achieve compromise on vital national issues can be seen as a consequence of single-issue obstinacy. While the term “Wheelerism” is little known today, we are still living with the corrosive effects of single-use activism on American democracy.

Just imagine how our national political scene would change if elected officials were not worried about the influence of single-issue activists. How might the tough issues of our time actually get resolved if we approached them in a way that recognized the complexity of the issues we face? What if our politics recognized that most people live complex lives with a set of complex beliefs that are missed by reducing everything to a single issue? What kinds of democratic reform might help reduce the outsized power of single-issue activist organizations?

* * *

“There is no thing as a single-issue struggle because we don’t live single issue lives.”– Audre Lorde (writer, philosopher, poet, and civil rights activist)

This is part of our “Just Imagine” series of occasional posts, inviting you to join us in imagining positive possibilities for a citizen-centered democracy.