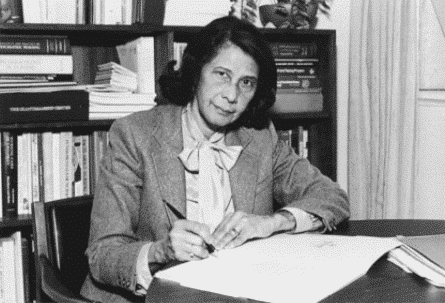

Virginia Apgar, via the National Library of Medicine

Virginia Apgar grew up in a family that faced medical challenges. One of her two brothers died of tuberculosis and the other had chronic health problems. Her family’s health issues led Virginia to pursue medicine as a career. There were few woman physicians when Virginia began her medical studies in 1929 at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. Nonetheless, Virginia excelled at her medical studies, graduating fourth in her class.

Virginia wanted to become a surgeon, but was discouraged from this pursuit by the college’s chair of surgery. He was worried about the employment challenges she would face as a woman competing for work in a male-dominated field during the Great Depression. Instead, he encouraged her to pursue a career in anesthesiology where felt she had the ability to advance anesthesiology practices to support new surgical techniques.

Virginia focused her interests on how anesthesia affected mothers and their babies. At the time, infant mortality had been on a downward trend, but the number of infants who died in the first 24 hours after birth remained fairly constant. Once a child was born, physicians focused on the health of the mothers, which meant that infants who were failing to thrive might be overlooked.

When she was asked by a medical student how to judge the health of a newborn, Virginia had an inspiration. She created a scale to assess the health challenges of newborns. The scale assessed heart rate, respiration, color, muscle tone and reflex irritability. Babies were given a score of 0 (distress), 1 (less than optimal), 2 (optimal). The beauty of the scoring system was the speed at which babies could be assessed and medical actions taken. The first score was determined one minute after birth. The Apgar scoring system, which bears her name, is now used worldwide to assess infant health status. The Apgar score helped reduce infant mortality dramatically.

The gender biases of the medical profession could have led Virginia to a life of resentment, but she chose instead to make a difference with her life. When she was denied access to certain fields of medicine, she developed new areas where her energy and curiosity couldn’t be denied. While she privately lamented enduring gender inequities, she nonetheless maintained that “women are liberated from the time they leave the womb.” While she is best known for the Apgar scoring system, she also went on to make significant contributions in preventing and treating birth defects. She established her niche in her medical career where she was able to make advances despite the gender-related constraints of the field.

Those who make a difference don’t let personal challenges stop them from their quest. They realize the futility of resentment and instead focus on the contributions they can make. People who make a difference are ambassadors of hope. They inspire others to think of what might be, rather than what has been.

* * *

“The very least you can do in your life is figure out what you hope for. And the most you can do is to live within that hope.” – Barbara Kingsolver (Author)

This is part of our “Just Imagine” series of occasional posts, inviting you to join us in imagining positive possibilities for a citizen-centered democracy.